Strawbridge, Mode of Baptism, Lenten Meditation (4)

In my ideal world, people would never skip through momentous occasions. They would be forbidden from moving on without first moving into that thing they experienced. I would sit around a fire and talk about the people I met, the food and drinks, the memorable conversations, the potential fruits of all that transpired, and how all of that now can change me as a person and those around me as a result. Then I would pass the torch, and we would go to bed late at night filled with stories in our hearts. But alas, one returns from a long trip, and is quickly immersed into all sorts of dynamics, catches up with 17 days of emails and piles of administrative things, and life resumes as if whatever you experienced didn’t happen.

I have come to realize that life is like that— and you do the best you can to retain, to write, to keep precise memories, and then embrace the new challenges. Meditation is a lost art. I miss the capacity to contemplate in our society. Perhaps Neil Postman saw all these things, and perhaps our amusement has killed our contemplative self. Mind you, I am a Kuyperian with the birth certificate to prove it. But I think it’s healthy to live in this tension, and I confess I live it daily.

Lancaster, PA

Undoubtedly, you begin to feel this immense tension when you deal with your mortality and those who are now immortal. Such was my trip to Pennsylvania. My arrival at the hotel in Lancaster around midnight was, for me, the realization that it was the last leg of my trip. But more than that, it was my ability to confront the death of a friend. In fact, the last time my feet stepped in Lancaster was to preach the funeral of a peer, a peer who functioned like a friend; no, he was my friend. He was the friend who would listen to my attempts at philosophizing counseling. He listened intently and engaged me as if I were one of his academic equals. But Gregg Strawbridge was a titan—musically, theologically, and pastorally. And I can only hope to be half the man he was.

So you can imagine that being in Lancaster to deliver the Winter Conference of 2023 was nostalgic. It was like I had been there before, even before the funeral. But, the reality is I had not been. He had asked me two years in a row to speak at the conference, and I declined. I had a dissertation to write. I thought I had so much time. I stood and lectured about the Church and Family at the glorious stage of an old seminary that carried the legacy of Philip Schaff and John Williamson Nevin. The environment was noble, but my noble friend was not there. He would have loved to opine about Mercersburg theology, a group of scholars whose sacramental thinking shaped so much of my own intellectual ethos.

Still, lecturing in his absence was meaningful. It was a debt I owed him. I was honored by the gracious audience and their questions. My topics reflected some of my thinking on the centrality of the church and the ecclesiastical nature of liturgical sexes. If the Church functions as a paradigmatic institution, then marriage roles should be clearly defined. And lo, I Corinthians 11 lays this out in glory; the glory of woman and the headship of man.

The Q&A was invigorating. After nine previous lectures, interacting with hundreds of people, and dozens of questions, I actually felt that my mind was sharpest, though my body was most weary. I elaborated on what I consider to be the allure of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy with their danger of producing monological beings susceptible to tyrannical rule both in Church, State, and Family. That discussion needs to be further developed since I first heard the observation from the lips of James B. Jordan over a decade ago.

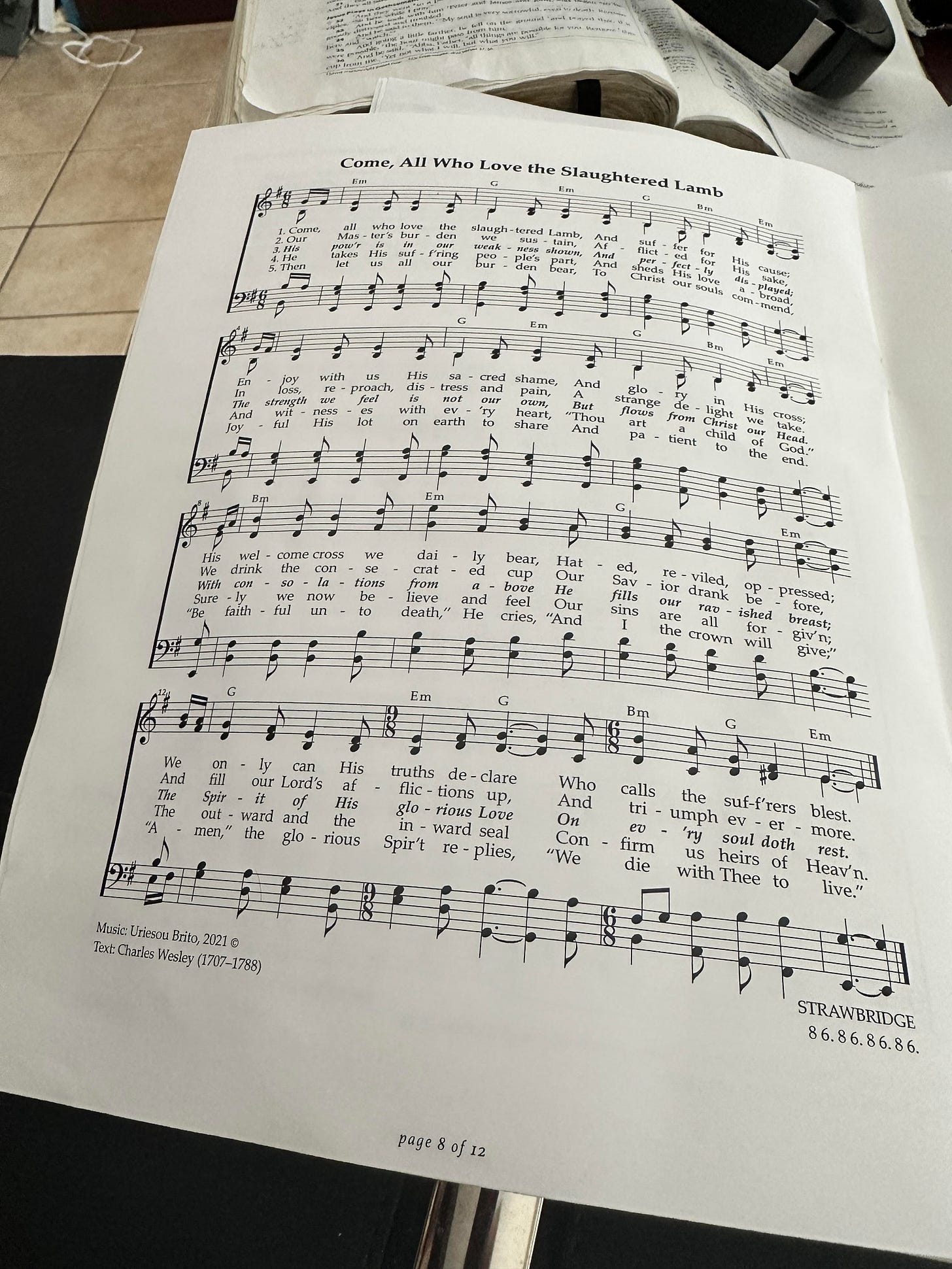

If that occasion stirred me emotionally, Sunday morning moved me further still. I taught Sunday School and preached the morning sermon. It struck me that the pulpit was the place that housed Gregg’s words with such precision. It was the place where he touched bread and offered wine. The sacraments, which are memorials, but deep reflections on life and death, provided me with heartfelt sentiments. They were accelerated when Gregg’s widow, Sharon, came and sat next to me to sing one of the Eucharist hymns. I didn’t encourage them to sing anything in particular, but they honored me with a tune I wrote for John Wesley’s Come All Who Love the Slaughtered Lamb. It was a tune I wrote explicitly in honor of Gregg Strawbridge. We sat there, and I sang loudly as this dear saint sang boldly next to me.

That was a momentous occasion. I don’t want to forget it. I want to remember it and savor it for a little. I hope I will.

Sincerely,

Uri Brito

~~~

A New Paid-Subscriber episode is available on the Perspectivalist podcast. I spent some time delving into the mode of baptism. You can pay $1 a month to receive these special podcast episodes.

Note: Thanks for reading these Lenten meditations. They are much more contemplative in these early stages. They will lead into practical details later, but for now, the groundwork for the necessity of the journey is laid. I trust you have embraced it.

Lenten Devotional, Day 4

Lent is an extended practice in meditation. The fourth-century father, Ambrose, once noted that “looking on Jesus will strengthen patience under the cross of Christ.” How often do we take time during the year to meditate under the cross of Christ? We may say we think of the cross, and we may hear an occasional sermon on the cross, but when do we make the cross the sine qua non of our faith? Do we meditate on a cruciform theology? If we did, how would that impact our contemplative life?

The Psalmist took the time to meditate:

"Within your temple, O God, we meditate on your unfailing love."

It is the church's call to take time and ponder the love of God, to meditate on his steadfast love for his people. And no love is greater than the love that would give his life for the sake of a people (Jn. 10:15). Thus, to meditate during Lent is to look deeply at the cross of Jesus, to strengthen our patience and to train ourselves in the habits of love.

We cannot think about the birth, the cross, the empty grave, and the ascension simultaneously. Thus, the church structures the year so that each part of Jesus’ life is emphasized. In other words, the calendar allows us to meditate on the whole of Christ in small doses. The crucified Christ is inexhaustible in riches, and even eternity will suffice to contemplate all his glory and grace. But Lent gives us a season of meditation on his unfailing love at Calvary.

In particular, Lent is a corporate focus on the cross of Christ and the journey to that cruel tree. As we face with boldness the next thirty-seven days, we must remember that Lent is a gift from God, a gift of time that we are to steward well.

As we prepare for worship this coming Lord's Day, we would do well to remember God’s unfailing love. In love, our Lord Jesus gave his body for us so that we would be made whole. Use this season. Don’t let it pass in vain. Meditate on his love. Indeed there is no greater love known to man than the death of the God/Man for man's everlasting life.

Prayer: O blessed Jesus, whose life was given for us and whose blood was shed for our redemption, have mercy on us. We forget your love too often; we are selfish with our time, and your cross is so easily removed from our meditation. But do not forget us, O Lord. Our hope is in you. Our life is in you. While we too often seek the love of other things, You never cease to love us. Keep us close to the cross, for under that tree of death, we will find the fullness of your life through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.

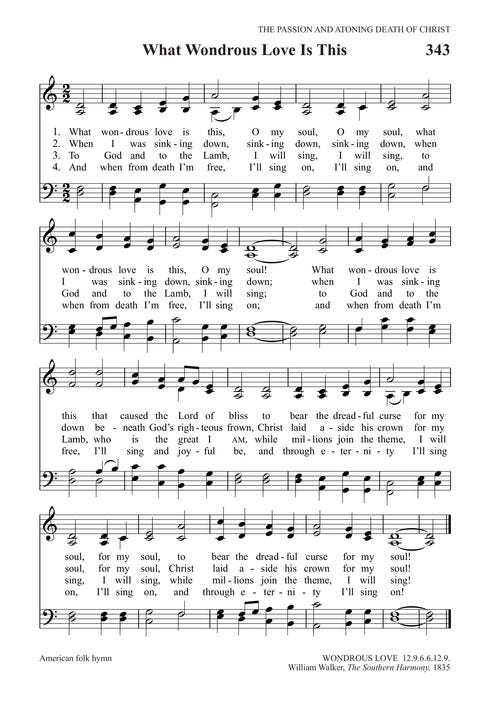

Hymn of the Day: What Wondrous Love Is This