Why John Frame Is Cooler Than You Think

And some book notes and traveling updates.

One of my most cherished moments in seminary was being exposed to John Frame’s definition of theology. For Frame, theology was defined as “the application of the Word of God by persons to all areas of life.”

There were always academic dimensions to theology, but theology was something immensely practical. It brought people to a "state of spiritual health." This definition is helpful because,

“Theology is thus freed from any false intellectualism or academicism. It is able to use scientific methods and academic knowledge where they are helpful, but it can also speak in nonacademic ways, as Scripture itself does – exhorting, questioning, telling parables, fashioning allegories and poems and proverbs and songs, expressing love, joy, patience . . . the list is without limit.”

I have repeatedly used this definition and learned to appreciate it even more as a pastor. The Spirit does not implant in us an application out of nothing. Instead, theology needs to be made applicable and relevant by pastors to parishioners, and from parishioners to other parishioners.

It is also freeing to consider this definition in light of the theological illiteracy in our day. Indeed, we wish to see the church grow in biblical knowledge, but this definition means that a pastor can instruct even the newest convert theologically on how he ought to live. He can apply the measurements of the temple in Revelation 11 to find precise applications for God's people.

Frame’s definition accentuates the pastoral task by calling pastors to ask consistently, "How Now Shall We Then Live?" In this sense, as Frame has argued elsewhere, unless theology is practically applied, it has not become true theology.

On the other hand, one who engages in theology must first understand it before applying its principles. We have seen our share of faulty applications in the realm of the home and the church. Therefore, to properly grasp this definition of theology, one needs to be familiar with theology.

David’s battle with Goliath was more than a remarkable example of how we can overcome difficulties in our lives, but also how God can use the weak to defeat the strong, and how a nation needs to put its trust in God rather than chariots, and how the Church needs smooth stones of faithfulness to destroy the wicked. There are individual and corporate obligations involved in that straightforward narrative.

Theology prepares us to ascend with our Lord. In that reign, we can learn to apply this rulership in all areas of life. By applying our theology, we become ambassadors for it. Theology is life, and life is theological.

Notations

Yes, he’s a dear friend, but Rich Lusk’s Measures of the Mission is an excellent summary of theological orthodoxy and a great way to introduce folks to what we believe in the CREC. His section on the Ascension (chp. 5) asserts that the Ascension of Jesus is belittled in the evangelical church. It is more likely that a “modern evangelical church will celebrate Mother’s Day or Memorial Day rather than the ascension” (67). He notes that Daniel 7 is not a prophetic vision of the Second Coming but the Ascension. The Son of Man is taken up to the ancient of days instead of coming down. The ascension, he argues, comforts God’s people because a “human being is now ruling in heaven; the dust of the earth now sits on the throne of God” (72).

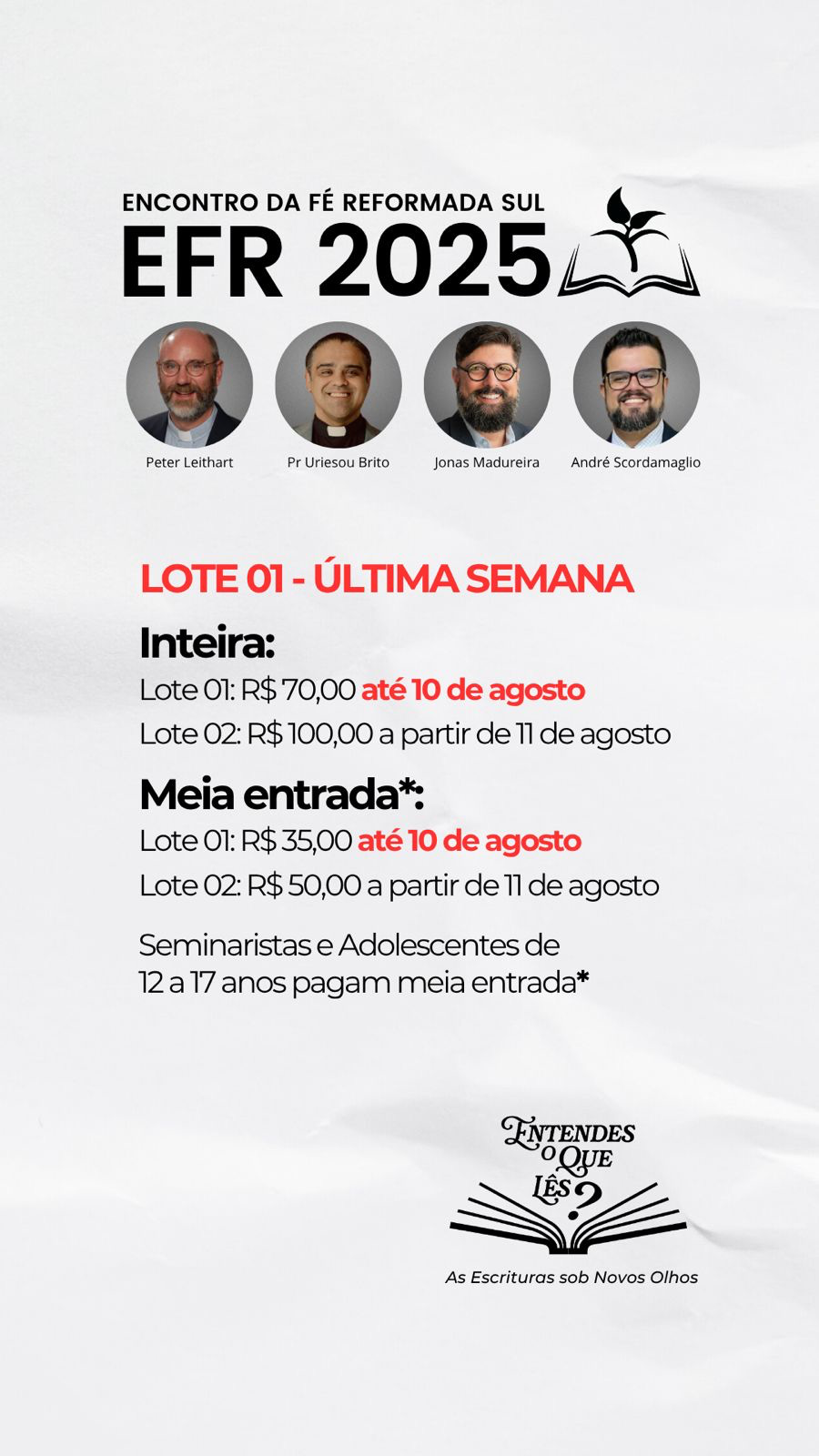

Reading Peter Leithart has been my part-time job for over 20 years. He and I will be headed to Brazil in a couple of weeks to speak. I have spent so much time with him and heard him lecture so often that I can see him uttering every word in his writings and can capture the intonation of those utterances. In the Theopolitian Liturgy, he gives the punchline at the end of his introduction: “The liturgy is itself the first transformation of culture. The Liturgy is culture transformed into kingdom” (xx). According to Leithart, liturgies are shaped by God’s word, but we must first know the Bible to think liturgically (xii), which will require immersion in biblical culture. In the liturgy, the common becomes a means of redemption for God’s people. He concludes beautifully:

Time is choreographed for liturgical dance, and the world exists to give us a share in the joy of the Father (xix).

C.S. Lewis’s appetizing introduction to Athanasius’ On The Incarnation is superb, but getting into Athanasian orthodoxy is even more delightful (the translation I am using). In the first section, he argues that wickedness involves the worship of idols. And that the more the Greeks and Jews mock our Lord and his work, Christ provides a greater “witness of his divinity” (49). In the second section, he articulates a doctrine of creation that defends the idea that God “ordered and created all things” (50) against the Epicureans, who argued that all things came “spontaneously without creation” (50). Athanasius writes to produce pastoral wisdom so that our piety might be multiplied in our reflection and service of the incarnate Christ.

Jeff Meyers argues in his 2007 lectures at the Biblical Horizons Conference (two years before I joined the fun) that Colossians is an apologetic for baptism (Col. 2:11-12). The book serves to illuminate the baptismal identity given to the saints. The circumcision of Jesus was his death, but the baptism is our union into his death and resurrection. He argues persuasively that Colossians 2 parallels Romans 6.

Nuntium

I will be invocating at the National Conservatism Conference in D.C. next week:

And then headed to South Brazil for our Theology Conference:

Good for you on reading De Incarnatione, but I always have to remind people (because no one ever told me until far too late) that it's the 2nd half of a two-part treatise. Don't forget to dive into the first half, Adversus Gentes, for a lot more context and thought provoking!